It is easy to compute a number for repurchase price per share: cash spent on buybacks divided by number of shares retired.

For better informed decision-making, a more complete economic analysis of share repurchase programs that take place over time should reflect both (1) interest income, which has become more meaningful in the current higher rate environment, and (2) dividends, if applicable.

Keeping track of these factors is particularly important when comparing structures with different cash deployment or share delivery profiles — e.g., comparing an ASR to open market (OMR) or enhanced open market (eOMR).

Earning Interest

Whether a company buys 1 million shares on January 1 for $100 million, or 1 million shares on March 31 for $100 million, both purchases would be reflected in its quarterly “shares repurchased” table the same way: 1,000,000 shares retired for $100.00 purchase price per share.

But these are not economically equivalent! With T-bill rates above 4%, deferring the repurchase for 3 months would allow the company to earn $1 million on its cash before it is deployed (ignoring taxes).

Compared to the $100mm spent in January, the March repurchase would have an economic cost of $99 million ($100mm minus the $1mm interest earned). The economic repurchase price on March 31 should be adjusted down by $1.00 per share to $99.00, to be comparable to $100.00 on January 1.

Saving on Dividends

For dividend payers, another adjustment is required. Consider the case of the $100mm repurchase that occurs on January 1 or March 31. Let’s assume that there is a dividend payment of $1.00 on February 1. In the case of the January 1 repurchase, the issuer would “earn” the dividend on the shares purchased. This would reduce the net cash spent by that amount (e.g. $100mm – $1mm dividend earned = $99mm net cash spent). The March repurchase occurs after the dividend payment and so doesn’t have this benefit. This difference in the net cash spent is important when comparing the economic price per share for the January repurchase versus March.

ASR Price Stickers vs. Real Economics

ASR pricing appears attractive right now because of cyclically high discounts to VWAP. While the ASR has its place in repurchase programs (monetizing volatility for a high guaranteed discount, upfront share retirement etc), comparing its discount to expected discount in open market or enhanced open market (eOMR) approaches is not correct.

Part of an ASR’s discount comes from the issuer prepaying the program’s dollar amount. The bank earns interest income on this cash until it buys shares in the market. In a competitive process, a bank will reflect the value of this income to the issuer as part of the VWAP discount.

In considering an OMR or eOMR, we need to take into account the interest that an issuer earns on its own balance sheet before each share is purchased.

Because the ASR VWAP discount includes the interest benefit, it optically overstates the value of the structure relative to the standard calculation for OMR / eOMR.

Similarly, an ASR discount can understate the value of the structure for dividend payers. Upfront share delivery can result in retiring more shares before a dividend record date compared to a comparable-duration OMR or eOMR plan, and in comparing prices the ASR repurchase price should be reduced for dividends saved.

Interest and dividends need to be accounted for in analytics used to decide share repurchase method and structure. Matthews South has spent nearly a decade developing analytics to compare programs on an apples to apples basis.

A Super Simple Example: ASR vs. OMR

Let’s compare a basic ASR with 100% upfront share delivery against a dollar-cost averaging open market plan on a hypothetical $100 non-dividend paying stock, in a 4.5% interest rate environment.

Our ASR pricing model shows a VWAP discount of 0.90% for a 3-month fixed-maturity ASR (assuming 30% volatility and no bank profit). 0.56% of this discount is due to interest, and the remainder to volatility.

Compare an open market repurchase that buys $1.56mm per day for the 64 trading days (3 months, same as ASR). In the open market program, the company deploys $100mm ratably over 3 months: it earns 3 months of interest income at a 4.50% rate, on an average balance of $50mm, or $562k total. Effectively, the company spent $99.44mm on a net basis compared to $100mm in the ASR.

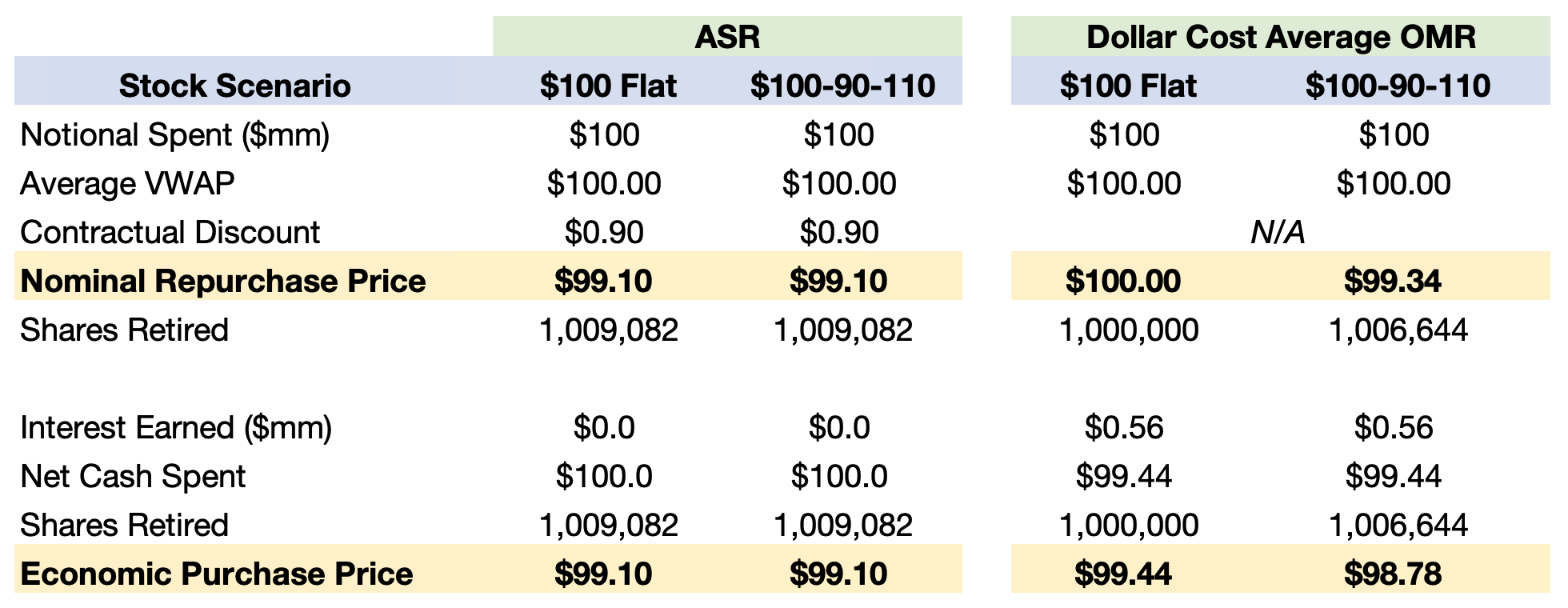

The below table compares the results of both programs in two stock price scenarios: (1) the price is flat at $100, and (2) the price rotates every three days between the prices of $100, $90 and $110. In both cases, the arithmetic average is $100, but dollar cost averaging in scenario (2) confers the benefit of buying more shares when the stock is lower and fewer when the stock is higher.

The ASR repurchase price is $99.10 in both scenarios, and no adjustment for interest income is needed; it is embedded in the discount.

Looking only at the nominal repurchase price, the OMR program seems to underperform. But once the $562k of interest income is reflected, the repurchase prices drop by $0.56 per share, and the OMR looks better in the volatile environment.

ASR vs. eOMR

To further illustrate the need to look beyond nominal pricing concepts like “VWAP discount,” we’ll look at slightly more complex programs and incorporate actual transaction costs (i.e., bank PnL). We’ll compare a 2-month minimum / 4-month maximum ASR to an eOMR with the same parameters.

Imagine with a 30% volatility, a company can execute an ASR with a bank at a 2.50% VWAP discount. For the eOMR, there is no fixed discount but a “random walk” Monte Carlo simulation at 30% volatility reveals an expected discount (comparing repurchase price vs. average VWAP on each random walk path) of 2.24%, apparently inferior to the ASR.

But a full economic accounting of the eOMR should take into account the interest earned on cash before it is spent. Since shares are purchased over a 3-month period (plus or minus), once again the issuer earns ~4.5% on an average balance of $50 million for a quarter of a year. This is $562k of interest, which effectively reduces the cost of purchase / increases the discount by 56 bps, to 2.80%.

It is this 2.80% interest-adjusted expected discount for the eOMR that is comparable to the ASR discount of 2.50%. In this particular case, the comparison reflects the fact that the ASR was priced to 0.30% profitability for the bank. By contrast, the eOMR need not come with this cost — Matthews South has advised on a number of low-cost eOMR programs that have helped issuers avoid high bank commissions in the structure.

Conclusion

Numbers have the ability to mislead us. As it relates to share repurchase, especially with higher rates, it is critically important for issuers to take a complete economic view of their share repurchase transaction alternatives, including variables that don’t necessarily make it into a pricing term sheet or even into the repurchase price reported in the 10-Q table.

Matthews South: Comparing Apples to Apples since 2014.

Personal Views: The views expressed in this report reflect our personal views. This blog post is based on current public information that we consider reliable, but we do not represent it is accurate or complete, and it should not be relied on as such. The information, opinions, estimates and forecasts contained herein are as of the date hereof and are subject to change without prior notification. The large majority of reports by us are published at irregular intervals as appropriate in our judgment and ability to produce, so updates may not be made or available even when circumstances may have changed.

No Offer: This analysis is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security in any jurisdiction where such an offer or solicitation would be illegal. It does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual clients. You must make an independent decision regarding investments or strategies mentioned on this website. Before acting on information on this website, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances. You should not construe any of the material contained herein as business, financial, investment, hedging, trading, legal, regulatory, tax, or accounting advice. The price and value of investments referred to in this analysis and the income from them may fluctuate. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur.