A 15% greenshoe is considered market standard in the U.S. convertible bond market. The greenshoe feature derives from the equity market, where it is also standard. Debt markets — high yield bonds, investment grade bonds, term loans — do not use it.

We provide data to help issuers assess the tradeoff between the potential marketing benefits of the greenshoe and the capital structure uncertainty (and incremental complexity) of having a greenshoe.

How Big are Greenshoes?

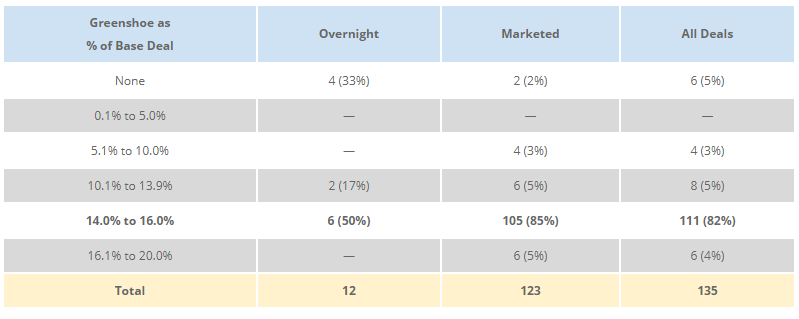

Data on the frequency of different greenshoe sizes in 2020 YTD indicates that while the 15% size is the most prevalent structure in the market, it is not universal:

The absence of greenshoes in overnight deals is not surprising. Many overnight deals are at-risk “bought” transactions, and banks target pricing that enables them to redistribute only the base deal and de-risk their commitment (making over-allotments superfluous). However, even in traditionally marketed deals, there is some dispersion in the size of greenshoes.

How Often Are Greenshoes Exercised?

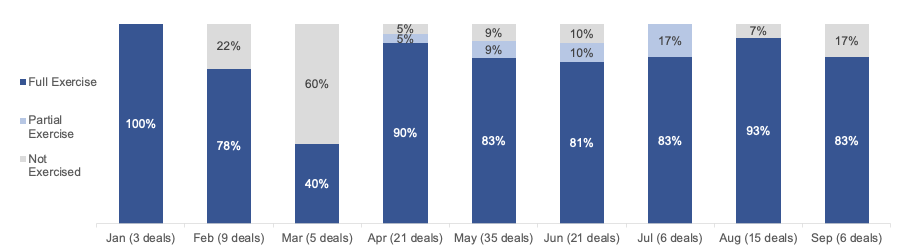

In this year’s 121 marketed deals with greenshoes, 101 (83%) were fully exercised, 7 (6%) were exercised in part, and the remaining 13 (11%) were not exercised at all.

Drilling down by month, greenshoe exercises occurred at a very high rate except for the period of market turmoil triggered by Covid-19. This is especially true of deals that were priced shortly before the market sell-off in late February / early March.

Greenshoes generally behave as we would expect: (1) most of the time they are exercised, but (2) in periods of market stress, there is a meaningful risk that proceeds (and related leverage) are lower. Issuers need to be prepared for either outcome to their capital structure and cash balances.

What is the Relationship Between Pricing and Greenshoes?

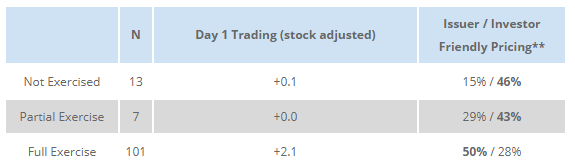

We also examine pricing / valuation metrics that are associated with greenshoe exercise. For reference, issuers are often told by bookrunners that pushing pricing more aggressively within the marketing range can jeopardize the likelihood that the greenshoe will be exercised.

Two patterns emerge:

- First, greenshoe exercise tends to be positively correlated with deals that perform better on their first day of trading (+2.1 vs. approximately flat). This is as expected: if a bond trades up, there is no need for banks to support the deal and the greenshoe should be exercised.

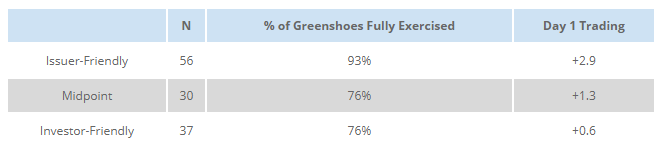

- Second, and less intuitive, is that greenshoe full-exercise tends to be associated with more issuer-friendly pricing outcomes (lower coupon / higher conversion premium) within the price talk. If issuer-friendly pricing outcomes within the price talk always implied more aggressive pricing outcomes relative to other deals, this relationship would be reversed.

This phenomenon may be more about convertible marketing processes than greenshoes. Deals that price towards the “tight end” of the range tend to trade up more (and have greenshoes exercised more often) than deals that price towards the “wide end.”

A likely explanation is that price talk can be “sticky”: once price ranges are announced to the market, in a one-day marketing effort it is difficult to push beyond the tight end of the stated range (and issuers may be satisfied with any better-than-midpoint outcome). If this is the case, then tight-end pricing might be evidence that even better pricing would have been justified. The result would be that bonds trade up and have their greenshoes exercised.

What is the Right Greenshoe for a New Deal?

Greenshoes can be a useful pricing tool. By enabling the bookrunners to buy bonds without capital risk if they trade down, a price-sensitive issuer might use a greenshoe to optimize its position on investor demand curve when pricing decisions are uncertain (i.e., the market may be comfortable improving coupon from 0.500% to 0.375% because the deal will be downsized from $575mm to $500mm if those terms are worth slightly less than par). And the data above shows that the expected economic cost of granting the greenshoe option is relatively modest: ~83% of the time, the market gets an extra 15% of deals that trade up 2.1 points. This equates to about a quarter of a point of trading value on the whole deal, or ~6 bps of coupon.

However, greenshoes may not be strictly necessary. Our recent transactions for Etsy and PROS Holdings both involved marketed offerings without greenshoes, and both priced well (Etsy priced at the tights: 0.125% up 52.5%, and PROS Holdings at the mids, 2.25% up 32.5%). Issuers may value capital structure certainty (i.e., knowing precisely the amount of leverage after a deal), may have board / governance constraints, or may prefer documentation and process simplicity.

The decision to include a greenshoe, and the size of the shoe, is a discussion worth having based on each issuer’s objectives.

Related Articles

Convertible Debt Accounting Update