Companies in the S&P 500 alone spent $770 billion in the past four quarters on share repurchase. The majority of this buyback was executed through open market repurchases (“OMR”), including 10b5-1 plans. In OMR programs, the broker, as an agent of the company, executes the instructions provided and earns a commission.

Given the significant amount of share repurchase done via OMR, issuers are interested in measuring the performance of their brokers. In any fee for service business, the client should routinely evaluate the quality of the service provided. This is especially true when there are many providers of the service and the switching cost to a better provider is low.

Traditional Broker Benchmarking

The most widely used method for evaluating a broker for its rotation is to 1) compare the average price per share they achieved against the average daily 10b-18 VWAP (“Program Beat”) and 2) compare their daily average VWAP against the daily 10b-18 VWAP (“Daily Beat”). The Program Beat is generally considered the more significant measure because it shows how actual prices paid compared to the prevailing market prices during the broker’s rotation. The Daily Beat is seen as an indication of the broker’s trading acumen–a broker that on average beats the VWAP each day is considered to be a “better trader” than a broker whose average daily beat was lower or negative.

These two measures of performance also have the virtue of being easy to calculate. In fact, most brokers will report both statistics in the daily spreadsheet they provide the issuer.

This approach, however, is deeply flawed. It can provide a misleading picture of the broker’s absolute and relative performance. Further, it incentivizes brokers to overspend or underspend each day (relative to grid instructions) to show better on these (flawed) measurements.

Problem with Program Beat

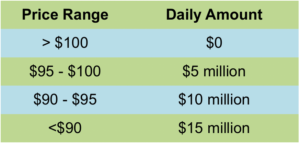

In most OMR programs, the issuer will buy more shares when the price is lower and fewer at higher prices. So, for example, a “grid” for such a program might look like this:

If the stock exhibits any volatility during the program period and moves between these rows, the average price paid per share will be lower than the average daily VWAP during the period. This is because the average daily VWAP weights each day equally, while the grid has the advantage of weighting days with lower prices more (by spending more money) than higher price days.

Therefore, all grids can be expected to have a positive Program Beat!

In fact, the Matthews South software can calculate the expected average VWAP beat for any grid using a Monte Carlo simulation. It is therefore inappropriate to attribute the Program Beat entirely to the broker’s efforts since each grid is inherently expected to have a positive Program Beat.

The magnitude of the Program Beat in an individual stock price path is generally a function of the volatility of the stock in that path and the grid’s construction. The more the stock moves around, the greater the daily spend variation, and, therefore, the greater the potential Program Beat.

Consider the scenario where the stock has low volatility and spends the entire period in one row. In this case, grid effectively weights every day equally by spending the same amount each day. The grid average execution price will be much closer to the average daily VWAP than a scenario in which the stock price crosses row boundaries multiple times. In the low scenario, there is virtually no trading acumen that can help the broker generate a meaningful Program Beat.

This path dependence makes the Program Beat across different broker rotations non-comparable. The broker that happened to have a volatile period is fortuitously advantaged, while the broker with a low volatility period is, conversely, disadvantaged.

Problem with Daily Beat

The Daily Beat is a very easy metric to measure and is often a focal point of broker-issuer interactions. This is especially true on days with large misses or beats (10 cents or more).

However, much of the Daily Beat is simply a function of variations in the intraday trading pattern versus the average volume pattern. This difference can make it either inherently difficult or easy for the broker (who understandingly tends to trade according to average volume patterns) to match or beat daily VWAP. For example, consider the implication for the broker if the historical pattern is for 30% of the daily volume to trade in the first two hours but on a given day only 20% of volume trades in the time period. The broker would have unwittingly overweighted the first two hours, by allocating 30% of the day’s spend. This could be beneficial to the broker’s Daily Beat if prices were low then relative to the remainder for the day. But, the opposite could be equally true.

For the Daily Beat to be an objective indication of broker trading acumen, we have to back out the positive or negative impact of each day’s intraday volume variation. Calculating this “adjusted” Daily Beat requires tick-level analysis of each day’s volume profile. Matthews South’s software reports the “adjusted” Daily Beat to provide issuers with an objective measure of daily broker performance and one that is comparable across broker rotations.

Is the Broker Spending the Current Amount?

Brokers are assessed almost exclusively by the average price paid for the shares acquired and almost never on the fidelity with which they achieved the daily dollar spend objective of the grid. The lack of adequate consideration for spend accuracy is a significant oversight. This is because the underspending on one day means that the broker will have to overspend on another day to catch-up. If the underspend day had a lower price than the overspend day, the program’s final average price will be negatively impacted.

For most issuers, monitoring the daily spend fidelity is difficult because the stock may have crossed between rows over the course of the day. The proper spend amount for the broker would be a pro-ration of the row spends based on the proportion of the 10b-18 eligible volume that traded in each row’s price interval. Calculating this prorated spend amount requires access to tick-level trade and quote data. Most issuers simply don’t have access to this data.

New OMR Benchmark Paradigm

A proper evaluation of broker performance is only possible if the broker is measured against an objective benchmark. For example, a mutual fund’s performance versus the S&P 500 is a better indicator of the “value add” of the fund manager than the nominal returns of the fund.

Like investment managers, broker performance also should be compared against an objective benchmark. This approach normalizes for the unique path the stock takes in each rotation and makes it possible to compare brokers on an apples-to-apples basis.

The benchmark, for each broker rotation, is the average price per share that would have been achieved if a broker always buys at the 10b-18 VWAP price and spent the correct amount each day. Calculating the benchmark is computationally intensive because it requires applying the grid rules on tick-level data. Many stocks have 10,000+ individual trades each day.

Matthews South’s software automates the benchmark calculation for any OMR program:

- Accesses consolidated tick-level quote and trade data from the exchanges

- Applies 10b-18 rules to identify all trades that were 10b-18 compliant

- Applies OMR grid rules to each trade to determine the average price for all trades in each row and aggregate prorated spend for each row

Several clients have shared historical grids and execution data with us. In many instances, the objective rankings based on benchmarking were completely different than the client’s perception of which broker was best.

Conclusion

Evaluating brokers against an objective benchmark, calculated for their rotation, is a better way to measure performance. This methodology will allow issuers to fairly rank the brokers in their program and improve their program’s execution by choosing brokers that perform better.

Related Articles

Enhanced Open Market Repurchase

Five Common Questions about eOMRs, an Essential Share Repurchase Tool